How to talk like a startup investor

Category: Understanding startup investment

startups

We’ve talked numerous times about what investors are looking for in startups, their investment criteria and why entrepreneurs need to understand that all investors are looking for are returns. They invest money to make even more money when there’s an exit, IPO or M&A.

Although most entrepreneurs are aware of the above by now, there are still certain terms that they need to understand when they meet with investors and navigate through term sheets. To help with this, we’ve put together a list of clauses and terms entrepreneurs should know about before meeting with investors.

Key terms entrepreneurs should learn when fundraising

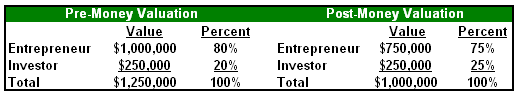

- Pre-money valuation: it refers to the valuation of a company prior to an investment. In other words, when a startup is raising money, its pre-money valuation is its value not including external funding or the latest round.

- Post-money valuation: it’s the company’s value after it has raised capital from external investors and the investment has been added to the balance sheet.

To illustrate the difference between both, we’ll use this example from Investopedia.

When startups raise capital, they sell shares to investors (and in some cases, also to employees). There are two main kinds of stock that are often part of term sheets and fundraising rounds:

- Common stock: stock that gives voting rights in certain matters of a company. It’s worth noting that owners of common stock are often the last ones to receive monetary compensation in the case of an exit or IPO.

- Preferred stock: this kind of stock is usually given to investors and it comes with certain rights attached. Contrary to common stock, those own these kind of shares will get paid first in the case of an exit.

We mentioned that preferred stock comes with certain rights attached. What follows are some examples.

How investors protect themselves in cases of fundraising

Photo | Investment Juan

- Liquidation preference: these type of clauses indicate that in the case of an exit (or IPO, M&A, etc), a certain multiple of the original investment per share is return to the preferred stock holders before anyone else (common stock holders, etc).

This example from Business Insider illustrates how liquidation preferences work:

Liquidation preference of 1X:

Imagine a VC that buys 50% of a company for $50 million, for a $100 million post-money valuation. If that company then sells for $75 million, the VC gets more than 50% of the $75 million. The VC gets his or her $50 million out first, and then half of the remaining $25 million ($12.5 million) for a total return of $62.5 million. The common stock holders split the remaining $12.5 million.

As the article goes on to highlight, liquidation preferences of 2X or 3X can really hurt founders and entrepreneurs in cases of liquidity events where the selling price is lower (or similar) to the startup’s valuation established in the last funding round.

- Anti-Dilution: this type of clause gives investors the right to maintain the same percentage of ownership in a startup even if the startup raises capital from different investors at a future time period.

Investors (or founders) don’t like to get diluted, and anti-dilution clauses allow them to maintain a certain percentage of ownership in the case of future rounds of funding.

- Tag along: this clause is often used to protect minority investors from missing out on opportunities to sell their investment.

This example from Return on Change helps understand how tag along clauses work:

For instance, let’s say during a startup’s series A raise, Investor A invests to own 5% and Investor B invests to own 30% of a startup. With the Tag Along clause, if after a year, Investor B has an opportunity to sell all or a portion of their 30% ownership to another investor, Investor A will also have the option to sell at the same valuation as Investor B.

- Drag along: drag along clauses are on the opposite side of the fence in comparison to tag along. It’s basically there to protect majority shareholders from having to receive permission from minority stock owners to sell their stock.

Using the example above, it would mean that if investor B wanted to sell its shares in a future round, investor A would have no choice but to sell his as well.

There are certainly many other terms often used by investors that entrepreneurs should know about, and we’ll cover those in future posts. This is a starting point for those currently fundraising or thinking about it, so that they can protect themselves from unpleasant surprises in the future.